Archive for the ‘Uncategorized’ Category

Nuvolari and the Augustas

Nuvolari and his Augusta

The other night at a holiday party, David Cooper, a car restorer of rather interesting tastes here in Chicago, and I were chatting about old cars. He tends to the esoteric, restoring 6C Alfa 2500s, Delahayes, and even Tatras, not to mention his bread-and-butter Land Rovers. He also hosts events of interest here in town. We get to discussing pre-war Lancias and he begins “Let me tell you a story Rene Dreyfus told me about Nuvolari and the Augustas…..” as follows:

Rosani and the D50s

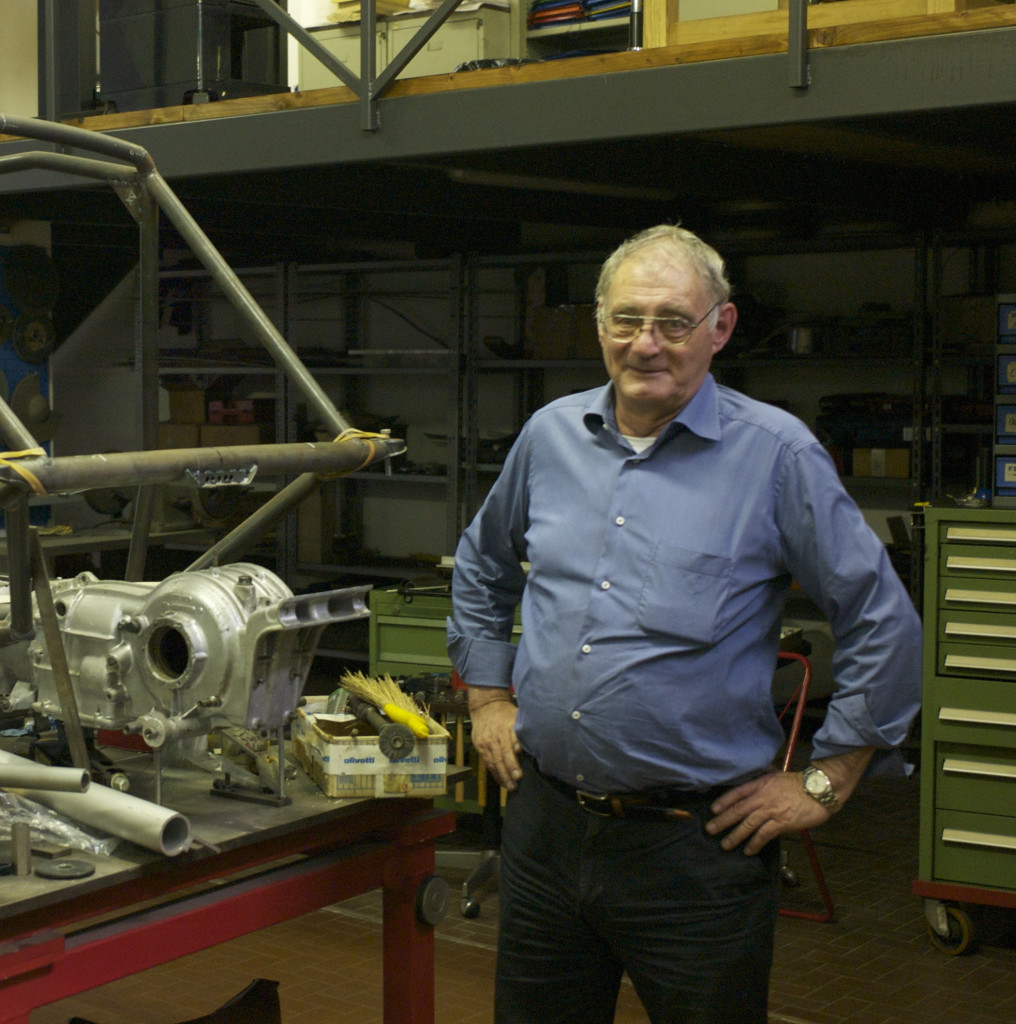

Guido Rosani in Torino

Guido Rosani is a designer, fabricator and mechanical wizard in Torino, long of the Lancia world. His father, Nino Rosani, worked at Lancia and became the architect for the company, and was involved in many of the company’s showrooms and facilities. Nino Rosani was, with Gio Ponti, the designer of the Lancia grattacielo, and was also on the board at Lancia. While a young child, Guido was able to visit the drafting rooms of the racing team, and is quite possibly, the last link with the magic of Lancia’s 1950s racing efforts.

With the help of Anthony Maclean, Rosani was able to build several D24s and D50s in the past two decades. These used original (and sourced) engines, with much else found or fabricated in accord with the works drawings which Rosani had access to. These cars remain difficult for the car world to classify, as they are more than replicas, in one sense “continuations” as close to the original fabric as possible. Detailed and meticulous care was taken in their manufacture, as Rosani once told me that even the myriad baffle system inside the gas tanks (with hundreds of rivets) was redone when the cars were made – attention pain in areas where no one would ever know.

In 2002 one of the D50s came up for sale, and Doug Nye posted on The Nostalgia Forum a history of the D50 recreation effort, with ample quoting from the Auction catalog text. For sharing knowledge, that writeup is here provided – with credit due of course to Mr. Nye –

Posted 16 August 2002 – 20:00 by Doug Nye (his text in italics, auction text follows, probably by Nye):

Robin Lodge has the first

A private collector has the second

Tom Wheatcroft and The Donington Collection have the third

The fourth is coming up for auction at the Goodwood Revival Meeting

A fifth is on the way and I’m not certain without double-checking whether that is going to be completed to Lancia-Ferrari trim, or whether it’s a sixth that’s going to be in that form. One is certainly being built with the merged-in ‘side tank’ Ferrari bodywork etc.For anyone with ambitions to own one of these wunnerful things – at a fraction of the potential price of the only two surviving (unattainable) real cars – this is the auction catalogue text. Please forgive the flowery hardsell old cobblers…

FORMULA 1 RACING SINGLE-SEATER

Chassis No: 0001( R ) Engine No: 13The legendary ‘side-tanked’ Lancia D50 was by some margin the smallest and fastest front-running Formula 1 car of its era in 1954-55, and was the only one whose potential performance was genuinely feared by the dominant force of those days – the World Champion Mercedes-Benz factory team. Former double World Champion Driver Alberto Ascari drove the D50 to pole position upon its debut in the 1954 Spanish Grand Prix – the last Championship-qualifying round of that season – at Pedralbes, Barcelona, and early in the non-Championship Formula 1 racing calendar of 1955 he won both the Turin and Naples GPs in splendid style.

One of the world’s oldest car manufacturers, Lancia always made cars for the connoisseur. The Lambda and Aprilia production models were among the most technically advanced cars of their day. Then in 1951 an almost standard 2-litre Lancia Aurelia Coupe finished a shattering 2nd overall in the Mille Miglia, beaten only by Villoresi’s mighty 4.1-litre Ferrari (after actually bettering the Ferrari’s times over the 1,000-mile public road course’s numerous mountain passes. This Aurelia model went on to win its class in the Le Mans 24-Hour race, finishing 11th overall.

Full of enthusiasm, the youthful company President, Gianni Lancia, authorised a comprehensive factory racing programme which produced the now immortal Lancia D24 sports-racing design. This spectacular car with flowing Pininfarina body, 4-cam V6-cylinder engine, rear-mounted transaxle gearbox and inboard brakes both front and rear, won the 1953 Carrera PanAmericana classic in Mexico (Fangio, Taruffi and Castellotti 1st, 2nd and 3rd) the Mille Miglia (Ascari) and the Targa Florio (Taruffi).

Against this imposing background, the stage was set for Lancia to enter Grand Prix racing. The Lancia D50 was the most innovative front engined Grand Prix car of the 1950s and arguably also of the previous 30 years. Designed by Ing. Vittorio Jano, legendary creator of the pre-war 8- and 12-cylinder Alfa Romeo racing cars, the compact D50incorporated a host of technical innovations, representing a clean-sheet-of-paper approach to Formula 1 car design which was of quite astonishing purity and elegance.

Its most obvious visual features were the two outrigged pannier fuel tanks slung from the chassis sides between front and rear wheels, not only to provide uniform fore-and-aft weight distribution and balance between full and part-consumed fuel load, but also because aerodynamic studies had indicated to Lancia that such fuel tanks between the wheels would smooth turbulent air flow, and reduce aerodynamic drag.

But there was much else besides. This was the first use in a World Championship racing Formula 1 car of a V8 engine and the first time that such an engine was used as a stressed structural member of the chassis frame. The power unit was mounted in the chassis only via the cylinder heads. It was angled to allow the driver to sit beside instead on top of the propeller shaft, thus lowering his seat to minimise the car’s cross-section and aerodynamic frontal area. Contemporary photographs show the drivers of conventional Ferrari and Maserati Formula 1 cars sitting several inches higher than Ascari, Villoresi, Castellotti and the other Lancia D50 drivers. Not only were these transcendant Grand Prix cars low-slung, they were also short and compact, the smallest of their era apart from the uncompetitive early-style Gordinis.

Transmission was via a 5-speed transaxle with syncromesh on the top 4 gears. Jano’s design team had also envisaged, but never finalised, a sequential gearbox and direct fuel injection. The beautifully finished, stubby little car weighed only 610kg. Delicate detailing abounded throughout, including intricately machined front suspension parts and inboard shock absorbers operated via drilled rocker arms. Every part was studied for lightness and the elegance of the Lancia craftsmen’s work followed the purity of the Jano team’s design. To many the Mercedes- Benz W196, the only true rival to the D50, appeared a more massive design, however masterfully executed.

The D50’s development took many months, before its belated debut at Barcelona in October 1954, but there the new works cars simply stunned rivals and spectators alike with their speed and handling. The Lancias, reported Rodney Walkerley in The Motor were “rockets on wheels”. In the race Ascari simply drove away from the field at the rate of 2 seconds a lap. At the end of the 9th lap, already 20 seconds ahead, Ascari was forced to retire due to oil on the clutch lining from a faulty casting.

On March 27, 1955, Ascari won the Turin Grand Prix with the improved D50A, with the sister team D50As of Villoresi and Castellotti 3rd and 4th. The D50s placed 2nd and 4th at Pau in April, then 1st and 3rd at Naples before confronting the Mercedes on May 22 at Monaco.

Ascari qualified his D50A on the front of the grid, then led momentarily before crashing into Monaco harbour in a cloud of steam. He survived, only to die within days, testing a Ferrari. Castellotti placed 2nd. Disheartened by the loss of their great Champion and exhausted by the effort and cost of their single-minded quest for racing success, Gianni Lancia and his mother Adele were losing control of their company. Castellotti – as a private entry – put the D50A on pole position for the Belgian Grand Prix at Spa in June but failed to finish.

With Fiat’s intercession, the Lancia Corse racing team was then closed down, and its cars and associated material presented to Ferrari – founding the World Championship-wining Lancia-Ferrari series for 1956. The original Lancia D50-series cars were dismantled and in large part broken up apart from two examples which survived in non-operational, partly incomplete form in Italian museums.

In the early 1990s great Lancia enthusiasts, Guido Rosani, born and bred in Turin and Anthony MacLean, an English lawyer living in Geneva, met and discussed a hugely ambitious project to re-create the D50s. MacLean had successfully campaigned a LanciaD24 sports car re-created in Turin by Rosani and colleagues in Historic events in Mexico, Tasmania, Sicily and throughout Europe. Rosani had a full set of Lancia drawings and much data, including details of the components of every car built, plus test-bed and race data, even including the spidery hand-written report by the Lancia team manager on Ascari’s victory in Turin in 1954.

Time, patience and help from Sir Anthony Bamford – who had preserved some original V8 engines and transaxles bought from Ferrari years before – laid the foundations for this project. Further searches in Italy unearthed more engines including, astonishingly, one complete original unit, still in its Lancia Corse packing case, complete with 1955 dyno tags. The rare missing Solex carburettors and correct Marelli magnetos were tracked down subsequently. No effort was spared to make the cars correct in the smallest detail. Not only the factory drawings and data were employed, but also the surviving complete car which the Lancia museum kindly loaned for inspection and dismantling.

Instruments were re-manufactured by Allemano, the original supplier, exactly to the original design. Wheels were re-made by Borrani to the original pattern. Some original suspension parts were located. The bodies were hand-made in aluminium in Turin by contemporary ex-Lancia craftsmen. The run of five cars to D50A specification today re-unites original engine and transaxle combinations which were first united in 1955, each individual chassis being given the correct original number with ‘R’ suffix to denote ‘reconstruction’.

Attention to detail has been extraordinary, including for example, hand manufacture of each of the delicately drilled and fretted fuel tank/strut brackets – five cars, eight brackets per car, forty in all, each one different to the next…The finished chassis and bodies were shipped to England where surpassing pains were lavished on re-building of engines and transaxles and race preparation of the chassis by Jim Stokes Workshops, well-known for many years for work on Alfa Romeo racing cars including the Alfetta 158, and also on the BRM V16. Only departures from original specification have been invisible and in the interests of either safety or longevity and practicality.

The original engine block proudly carries its Lancia date stamp – ‘11/11/54’ – and as rebuilt it has been dyno-tested to c.235bhp, closely matching the output recorded on an original Lancia test sheet, dated June 24, 1955, just a month before the transfer to Ferrari. The unit’s original originally fragile threaded valve stems have been improved upon, and the units built to offer several seasons’ reliable service without need for a re-build after every race as in 1955. The fuel tanks incorporate modern rubber bags to current FIA specification, while the multi-finned drum brakes now feature twin-circuit actuation. A small roll-over bar has been discreetly built-in. The cars have been track tested and set up by a well known historic racing driver and have been prepared to race – not merely as the beautiful artefacts they also, undeniably, are.

Of the five cars built, one is in the Donington Collection in England, another in a private museum while a third has been extensively raced over the past season. The car offered here is the last produced and is the property of one of the original partners in the project. It participated in this year’s Goodwood Festival of Speed and has been invited to take part in the Goodwood Revival Meeting the weekend of this sale. No pains have been spared to incorporate every lesson learned in building the previous cars and to make this car, which has no hours on it at all, apart from careful dyno and track-testing, as near as possible to the new car in which Ascari sat in 1955. It is finished in exactly the correct shade of deep Lancia maroon – rosso granata (?spelling??? DCN) – matching that of the hometown Torinese football club, Juventus.

This is a rare opportunity to own a truly stunning piece of Grand Prix history, ready to race, but also of the most exquisite museum quality in every aspect of its design and execution.”

If you feel so moved ring Bonhams on (44) (0) 207 393 3900 and ask for the Car Department. Tell them Doug sent you…

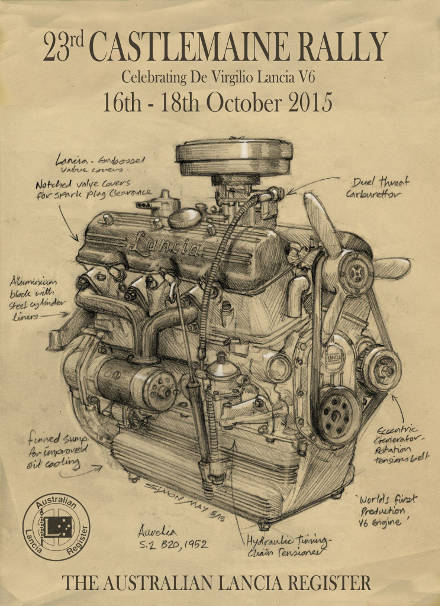

Castlemaine, Australia

Every two years, the Australian Lancia Club hosts a large gathering of cars and people at Castlemaine, a small town north of Melbourne by about 70 miles. While far from Italy, the passion of the Australians is quite strong, and their commitment to Lancia cars is remarkable. The gathering is quite large, this year with some 80 cars, ranging from Lambdas up to Betas, with almost every model represented. For the Lancia fan, it is a unique opportunity to see and learn about the full model lineup from Lambdas on.

It is a tradition of the Castlemaine reunion to invite a Guest of Honor, typically from overseas, to share Lancia lore with this community, and this year, I had the luck to be invited. In years past, they have had some wonderful visitors – Tariff, Villoresi, Gobbato, Sandro Munari, and Stefano Falchetto. In recent years, Angela Verschoor (Flavia book author) and Mike Robinson (head of Lancia Design Center for some time) have spoken.

While it is a long ways to go, the reception in Australia was quite warm. I stayed with Chris Long, one of the Committee members organizing the event, and we drove up to Castlemaine in his Lambda. There, all was well organized and the rally was held the weekend of October 17-18. I gave a talk on Saturday, which was well attended in a wonderful former sheep-shearing shed. The discussion was lively and the audience enthusiastic, and all went well.

The overall event was a great deal of fun and included visits to old farms, driving tours to wineries, a visit to Robert Bienvenue’s renovated church building (quite lovely), now a wonderful vacation home, and a special car shop in the area. Castlemaine benefited from a significant gold rush in the mid-1800s, and there is still some significant residual impact from those wonder years. The area is known as the center of Australian automotive hot-rodding, and we visited a shop, Up the Creek, run by Grant Cowie, where there were some extraordinary cars, including a 1914 Delage Grand Prix car, a Talbot Darracq, and numerous parts remade for Lambdas.

Bill Jamieson checking out the Lambda parts at Up the Creek, with Joachim Griese keeping a watchful eye over his shoulder

On Sunday, there was a large gathering of all the Lancia cars on the village green, and we were joined there by other Italian cars, Alfa Romeo, Ferrari, and the odd Lambo. Of interest was a man in an Alfa Guilia Super, who makes distributors for the older cars (including Aurelias) using a custom machined housing, but all contemporary Bosch components, including single points. These parts are both economical and readily available. Its worth getting for a spare to have, just drops right in.

Peter Renou generously took me under his wing, and was particularly pleased when I didn’t grind the gears on his Astura, which he kindly let me drive for the afternoon. After that, it was smooth sailing… more to come about the cars driven.

It was a delight to meet the Australian Lancia community, with many new friends, including (in no order) Chris and Anna Long, Peter Renou, Iain and Graeme Simpson, John Doyle (whom I last saw c. 1980 in Torino!), David and Peter Lowe a structural engineer who worked on Sydney Opera House), Rob Alsop, Marc Bondini, Bill Smith, Alan Hornsby, Paul Vellacott (remarkably at Hershey just the week before at the Awards dinner too!), Bill Jamieson (author of Capolavoro, a remarkably knowledgeable and modest Lambda expert), and Steve Boyle. There were several other Americans at Castlemaine, including Paul and Vicki Tullius, Neil and Elsa Pering, Steve and Lynne Petersen, all veteran Lancista from California, Paul and Lily English (bringing new energy to the fold) and Aurelia newbie, Jeff Hill. Angela Verschoor and several others came from Europe, including Joachim Griese, and John Millham and the Williamsons from England.

Noel Macwhirter brought his wonderful Aprilia and has since posted many great images of the event at Castlemaine 23. Take a look!

Overall, there are now few places for the historically interested Lancia community to gather – Sliding Pillar is one such event, held in Europe or England each year. Perhaps another could be Padova in Italy in the fall. Castlemaine deservedly must be on that list. The Australian Lancia community is strong and vibrant. They have been thoughtful about passing knowledge from one generation to another, a lesson for all of us to learn. Thanks to them for the invitation and the opportunity to share Lancia stories with them.

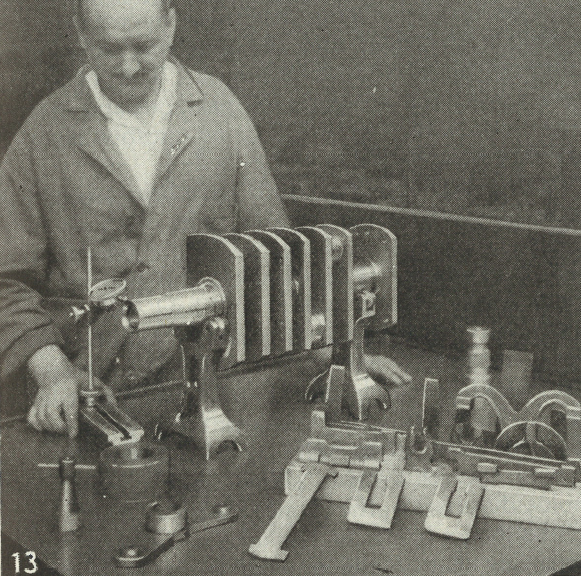

American Machinist

In the 1920s, the respected publication, American Machinist, printed several articles on Lancia and their manufacturing techniques. The publication had a history of printing long stories and in depth investigations into esoteric matters – one example was their tracing the Connecticut River Valley’s strong tradition in machining (home to a number of American gun makers) from its origins in a small Vermont village fifty years earlier.

Their in-depth investigation included many details about the Lambda, as they covered the manufacture of front suspensions, pistons, engine blocks, heads, crankshafts, brake drums, and its unitized body. Also studied was information flow within the company, as they viewed Lancia as a model for combining craftsmanship and industrialization under well-considered and detail-oriented management.

Written by J. A. Lucas, they ran about a dozen articles through 1928 and into 1929. Efforts to find their archives, or Lucas, have not been successful. Several years ago, a complete run of the articles was located at the U.S. Library of Congress. At that time, a reprint was made available although the original microfiche scans were of poor quality. Since then, originals have been located and better scans made. Two are available here – Lambda 1928 crankshaft and Features of the Lancia Plant 1928. The not-so-pretty but complete reprint can be found here: Lancia reprints.

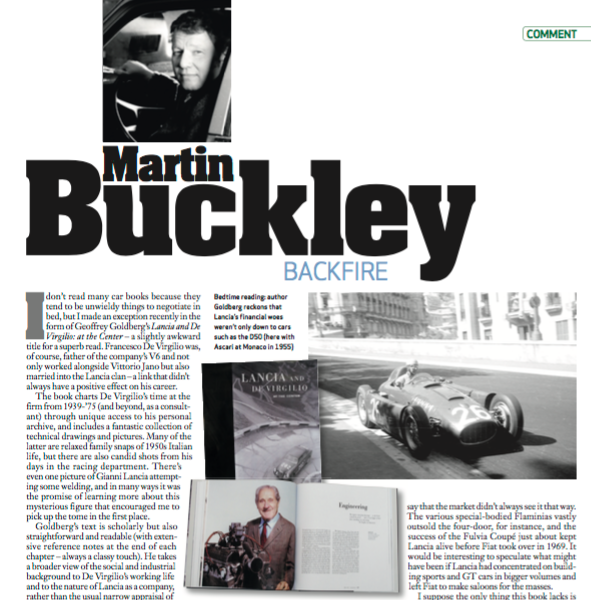

More book news

A few recent mentions:

In October, the Society of Automotive Historians gave its 2015 Nicholas-Joseph Cugnot Award to the book. The Cugnot Award is given to those deemed the best books in the field of automotive history published the year before, and in this case, the award was shared with J. Saoutchik Maître Carrossier, published by Dalton Watson Fine Books. In their comments, particular mention was made how these two books made history accessible and interesting.

Lancias at Ferrari

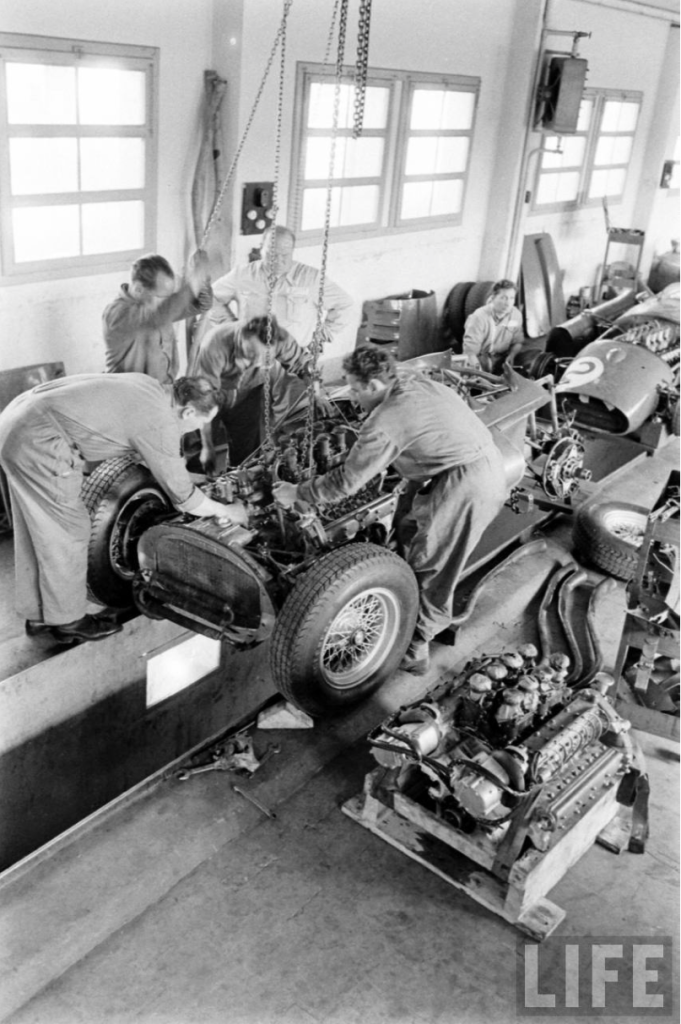

D50 engine being pulled. Photo by Tom Mcavoy, courtesy of Life Magazine

In 1955, Lancia gave their D50 race cars to Ferrari. Life photographer Tom Mcavoy photographed the Lancia cars at Maranello, being taken apart and worked on by the Ferrari team. The photos are dated 1956, but it may have been earlier.

Its an interesting set of photos, a moment of exploration and incorporation for Ferrari, looking at these cars as a group, that just descended on their shop. Not the normal way they did their work, but its clear they are hard at work figuring these cars out. A screen shot is below; to see them larger: ferrari source:life

Flaminia….crashing?

A rather remarkable video. Don’t know much about it. I recommend watch from the beginning but pay attention starting about 2:20. The explanation (translated) is:

“Driving around town should be safer at night. The virtual absence of traffic encourages certain drivers, whether by alcohol or overconfidence,to hurry as if there were anyone but them. The consequences can be fatal.”

anti-alpha

An email the other day from a friend mentioned going to Monterey with an “alpha-male” as company. Made me start to think – why did he mention that? Are Lancista different than other normal alpha-male-car-guys?

I’ve been giving a few talks recently about Lancia to a broad set of audiences. Some of these are cultural groups, heck, even a local Porsche club. People are interested about Lancia but want to know what this company was about. Its not easy to explain why we cherish these cars after so many years. The question is not easy to answer. Its actually rather perplexing.

Lancia (say up until 1990) doesn’t fit the norm for car companies. Yes, they were engineering focused, fully vertically integrated, but so were other companies. They were innovative… that’s important, but not enough to explain our fascination. They focused on well-developed chassis, far ahead of other companies. OK….that sets the stage, but these observations don’t complete the story. They doesn’t answer why we remain so passionate about these cars, or the joy we get from driving them.

The racing careers of the Aurelias, the D cars, the Fulvia and the effervescent rise of the later Lancias (Stratos, Integrale, etc.) all give a sense of the “little one that could”, and that is the heritage of the “thinking underdog” that the company represents. Is that enough?

There is the subtle and lovely pleasure of driving a Lancia, be it a Lambda, Aprilia, Aurelia, Appia, as well as later Flaminia, Fulvia, and Flavias. Its a pleasure that is hard to define, but could be described as the joy of balanced controls, enjoyment of torque over power, a suspension that informs but leaves you riding in comfort. Its relaxed driving instead of boy-racer. Its the joy of everything being thought-through and well considered. Its delight in the care taken in the design and making of the car. These pleasures seem central to the Lancia experience. One can understand how hard they must be for today’s marketing folks to appreciate.

Recently a non-Lancia friend and I took a Flavia 2000 coupe for a drive. He immediately remarked on the delicacy of its detailing. He saw softness, something he said was no longer in cars. That was an interesting observation, and I wondered if it synched with my sense perhaps Lancia was more sensitive to more feminine aspects of design than the masculine. Not sure what that means, but its a first thought. A brief look at the Fulvia adverts in the 1960s, so many of them featuring well-dressed women enjoying the car, suggests there may be something to this. Might Lancia have been an early company in their marketing cars for the emerging women drivers in the 1960s? Possibly so.

What about those alpha males? Lancias were for designers, engineers, professionals, lawyers, women…. doesn’t seem like an alpha group, does it?

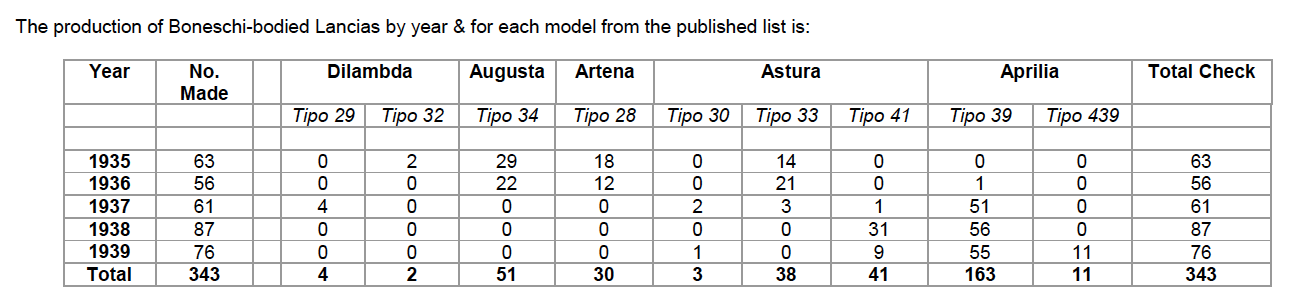

early Lancia numbers by Mayo

Paul Mayo is a Lancia lover from way back, having grown up with his father’s B20 in the 1950s. He was librarian for the Lancia Motor Club in England for many years, and has a deep interest in the older Lancias and in correct archival records. He shared these two documents, and asked that they be posted for wider distribution. The first is a recording of the 1948 list of Italian cars confiscated by the Germans posted in an earlier blog entry. He has gone back through the records and assembled a complete look at the post-war document, a treasure trove of information.

He also shared a compendium of the Boneschi Lancias, assembled through a detailed review of the Boneschi book, already published but hard to find. Put together, these documents expand our understanding of the early cars – and its information now available to be shared. Enjoy, with thanks to Paul for sharing.

1. The post-war list – I date it as 1948 (latest document date), which Paul calls ACI-47, as the ACI information is from 1947 and earlier:

2. Boneschi list – Here’s a teaser from his Boneschi analysis in the list (see pg. 12 of the document below):

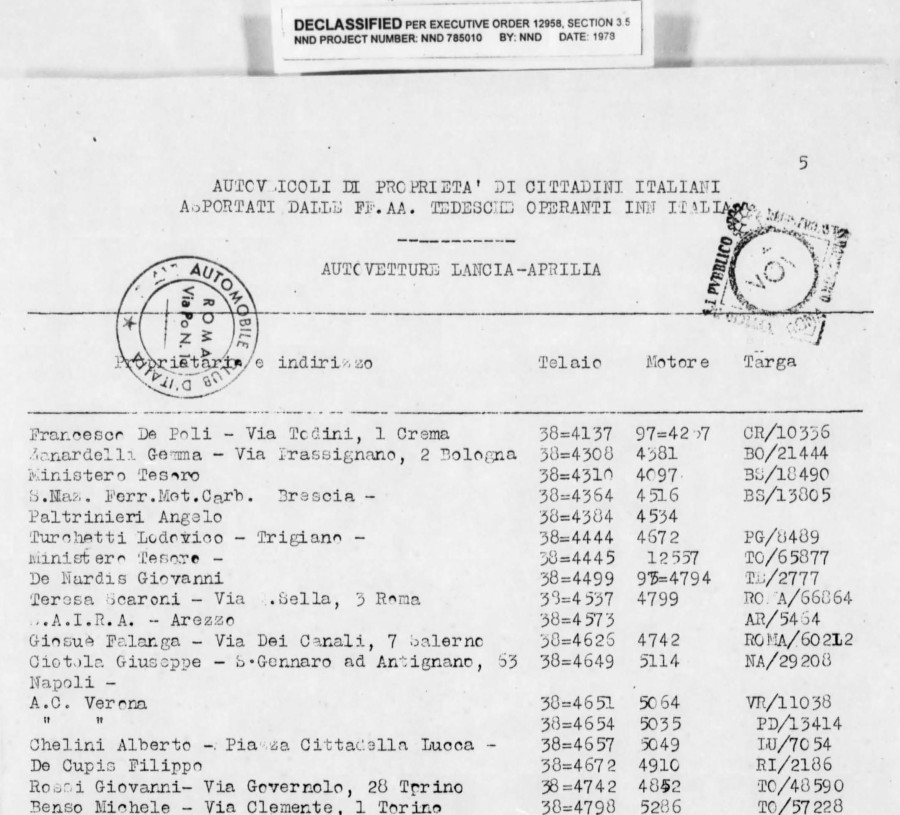

Early Lancia chassis numbers – 1948

Recently located was this document from the US government, postWWII. Its a 1948 document listing Italian cars confiscated by the Germans, declassified in 1978. What is interesting for the Lancia world is its extensive lists of Astura, Augusta, Ardea, and Aprilias, complete with owner’s names, registration, and more importantly, chassis and engine numbers. Also included is information for Lancia trucks, including Eptajota, Omicron, Ro and 3Ro. There are about 60 pages in total, with 26 pages of just Aprilia numbers. Originalinformation for early Lancias is hard to find, and this seemed worth sharing. Please forward to any Lancia registries.

Just a note – the PDF is large. In front are included a few pages of flavor with interesting period detail.